Why we stay in careers that aren't right for us

How to move through uncertainty and start exploring

If you enjoy this newsletter: would you mind sharing it with three achievers in your life? Thank you for your support 🙏

I was introduced to the idea of careers in sixth grade.

We sat in the library computer lab, huddled over bulging PC monitors, completing a lengthy survey about our interests, skills, and desires. “Do you like math?” I spent a while debating with myself before clicking the radio button affirmatively.

A week later, a report outlined my most promising career paths. Each student was asked to do a presentation to the rest of the class— complete with tri-fold display cardboard and WordArt banners— about their top choice career.

My prospects? Stock broker, followed by logistics consultant and librarian. I had no idea what to think of this.

At 11 years old, I was obsessed with two things: creative writing and building websites on Geocities. I spent my afternoons and evenings devouring novels and writing poetry books by stapling together folded sheets of printer paper. In a year, I’d spend the best summer of my life so far going to summer camp for creative writing.

And on weekends, I loved creating side navs with HTML iframes and using the magic of Javascript to change my cursor from a boring arrow into a confetti explosion. Alyssa from Lissa Explains It All was my all-time peer hero (you’d understand if you grew up as a girl programmer in the 90s). I didn’t know at the time that Software Engineer, Product Designer, and a variety of other professions would emerge in the decade to come, matching my passion.

Alas, the career assessment test and its all-knowing algorithm had determined my fate. I picked stock broker. I distinctly remember printing out a clip art image of a roller coaster (using the expensive color ink) because I had read somewhere that the markets can behave like a roller coaster. To prepare for the presentation, I interviewed a friend’s dad, a financial advisor, to get his take on the NASDAQ.

I got an A on the project— yet was left confused about why my future job was so out of sync with what I loved to do.

Jobs, careers, and callings

Amy Wrzesniewski, professor at the Yale School of Management, distinguishes between three attitudes about work: a job, career, and a calling.

A job is about working a 9-to-5 that’s a means to an end. We work so that we can support ourselves and our families with the income. No point in getting too attached; a job is merely a necessity. We consider ourselves fortunate to have a stable income and benefits.

A career introduces a new element to the work equation: upward progression. In a career, we’re not only doing our job today but also aiming to grow our skills so that we can move forward, get promoted, and achieve greater status and earnings in the future. We get a predictable trajectory and ladder. Ambition comes into play, as we yearn to be rewarded with success.

Lastly, a calling enables us to meld our personal sense of purpose, need for authentic self-expression, and paid work into one. We tell ourselves: “This is what I’m meant to do.” There is deeper meaning and mission embedded in our work.

The sticky path

If you’re reading this newsletter, you’ve likely found yourself in a solid career: one that pays enough, provides stability, and a steady path of progression. Or perhaps you’ve settled into a calling, only to wake up one day to realize it wasn’t so congruous with your self expression after all.

Maybe you have a spidey sense that this path isn’t right for you. And yet veering off seems like an impossibility.

As high achievers, we love sticking to paths. Why? First, it provides us with predictable certainty about what a good future looks like. Second, we’re disciplined people and love having a clear path of progression— whether it’s more skills, more money, or a higher title. And third, a well-charted path gives us a sense of belonging. If you’re anything like me, you’ve put a lot of hard work into this identity and community you’ve crafted. As someone who’s worked in tech for a decade, most of my friends have done the same. And after a while, we find ourselves immersed in an ecosystem that reinforces the rightness of the path we’ve chosen.

So what happens when we have a hunch that this path we’ve invested in so enthusiastically isn’t the right one for us at this particular stage in our lives?

After years progressing beautifully on the job, a private equity associate finds herself feeling lethargic and even irritated about daily tasks. A product management leader steps into even more responsibility at a high growth tech firm, scaling large teams working on exciting features— a goal he’s always had. And yet somehow, he struggles to get out of bed in the morning and spends weekly metrics meetings wonders if this is really the life he worked so hard to achieve.

Most of the time, we shrug off these feelings. Our identities are intertwined with the work that we do— and it’s too displacing to leave a perfectly excellent job without knowing for sure what an even more excellent version of that could look like for ourselves. We shudder at the prospect of having a gap on our resume. What would our network think? Perhaps we’d end up like that person we know who left their career path and never did find something better.

One day in the future, we promise ourselves, when we have the time and energy to do serious thinking, we’ll find what we’re truly meant to do. And equipped with rock solid confidence, we’ll be able to make a leap.

The myth of the true self

The problem with this premise: It follows the same thesis that my sixth grade career test did. By saying “first I’ll find what I’m meant to do,” we make an inherently flawed assumption: that there is a finite set of right answers.

In Working Identity, Hermina Ibarra describes the myth of the true self. Career advice is typically determined by a personality test— an assessment of our likes and dislikes, values, and preferences to uncover the ultimate truth of who we are:

By early adulthood, the theory goes, we have formed a relatively stable personality structure… [which] should form the starting point of any career search, because [it] determines what makes a good fit in a position and work environment.

In this context, therefore, successful career change hinges on understanding what critical personal attributes hold the key to a good fit so that we can target jobs and organizations that match.

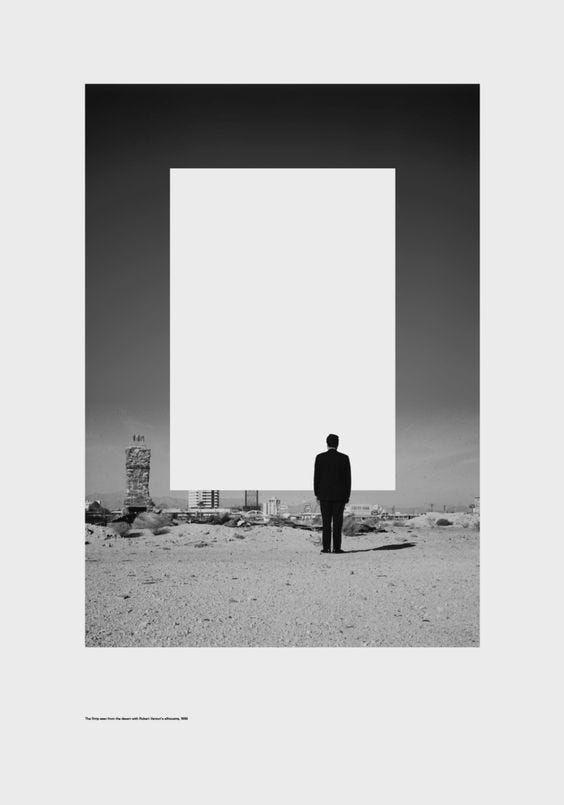

The challenge becomes: What if we don’t have that certainty yet in who we are and where we’d thrive? We keep our sticky work identities, the ones that we have carefully honed for a long time.

Far more often than not, the true-self approach— there is a ‘right’ career out there, and looking inward will give us the insight necessary to find it— often paralyzes us. If we don’t know what ‘it’ is, then we’re reluctant to make any choices. We wait for the flash of blinding insight, while opportunities pass us by.

Ibarra goes on to describe an alternative framework: one of multiple possible selves.

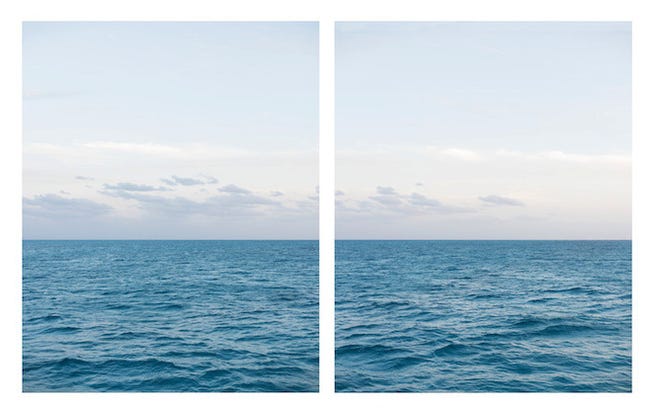

In contrast to the true self model, we can embrace the fact that our preferences and values change constantly throughout our lives. And that those ever-changing possibilities are best informed by direct experience.

Instead of creating a career blueprint and then constructing it, we test many fluid version of ourselves and ask: Which of these is most interesting to try right now? And how might I safely bring this possible self into the world so I can evaluate my assumptions?

By embracing a framework of multiple possible selves, we can then shift from a “plan and implement model”— charting out a pristine career path and then put it into action— to a “test and iterate model” by which we design safe experiments that test hypotheses in the real world.

This contrast resembles one that we see in software: waterfall vs. agile development. In the former, we write the full set of requirements before building, shipping, and expecting results. In the latter, we define the bare minimum before putting something out into the world— usually a prototype. We focus our attention on gathering learnings and incorporating them into the next iteration that we design.

How to design a new work identity

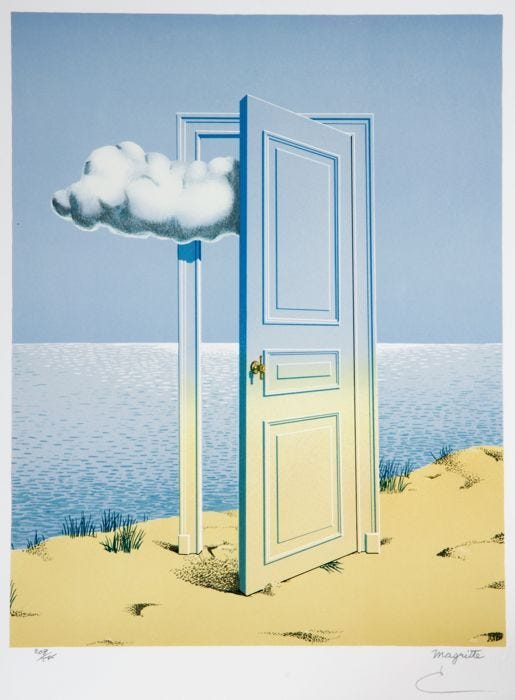

Shedding an existing work identity before we’ve shaped a new one is scary. As Ibarra puts it: “To be in transit is to be in the process of leaving one thing, without having fully left it, and at the same time entering something else, without being fully a part of it.”

In addition, our existing selves are always more concrete, vivid, and certain than the amorphous possibilities that are out there. It’d be crazy to expect someone to take a risky leap off the cliff without having handle bars on their future path.

Fortunately, we don’t have to quit cold turkey. For those of us with a stable job, we can get the best of both worlds: continue to work while testing— in small, gradual ways— the hypotheses we have about potential changes, an “identity on trial.”

The design process is iterative— from hypothesis to experiment to reflecting on learnings to inform the next hypothesis. What this process looks like:

Make space in our schedules. Experimenting takes energy— energy that our current role may not allow for. And so, the first step is to reduce hours and sources of stress, so that we actually have space in our weeks to experiment with future possibilities.

Keep a running list of hypotheses. Write down the inklings you have about possible future paths, even if they’re early and amorphous. Maybe you have a desire to be more artistic and creative in your work, or you’ve always had an intellectual curiosity about human psychology. What’s key here is not only writing down the hypotheses but also enumerating the assumptions we’re making. If you’re thinking of switching from financial analysis to software engineering, what assumptions are you making about why that role would be a better fit?

Design experiments. An experiment is a safe way to explore possible paths and test hypotheses. It could mean joining an online community of people who do the kind of work we wish to do and asking them what motivates and frustrates them. You could also start a side project to try on the work or take an online workshop to see if your curiosity sticks.

Reflect. After each experiment, be honest with yourself: what did you learn, and how does that change or refine your hypothesis? Schedule distinct moments in time (e.g. the week after an experiment) for reflection. This might mean having a conversation with a friend, mentor, or coach, or journaling and reflecting on your own.

Am I just going in circles?

After a few rounds of hypothesis testing, we may feel the temptation to quit experimenting. Where is this even going? we wonder. Maybe there is no better career for me out there. I should just be happy with what I have.

It’s natural to be squeamish about uncertainty; it’s uncomfortable! It can therefore be tempting to view career changes like crossing a street. As soon as the walk sign turns green and our foot steps off the curb, we want to briskly get to the other side. Arrival is more important than the journey.

What this might look like: We leave one job and embark on a hurried search for the next thing. We find a new role and breathe a sigh of relief; we’ve arrived on the other side of the road. And yet, in our first months on the job, the same spidey sense starts creeping into our minds: Is this actually what I want to be doing?

In reality, constructing a new work identity takes time. If it’s deeper change we desire, the transition won’t be so expedient. To ensure our financial stability, we may sign another offer quickly— but the need for true change is unresolved, and the effort must continue.

“The difficulty comes not from [circumstantial] changes but from the underlying and more difficult process of letting go of the person you used to be and then finding the new person you need to become in a new situation,” says William Bridges in the book Transitions.

If you’re considering a career change or in the midst of one, I encourage you to abandon the street crossing metaphor. Instead, see if you can view your transition as sailing across a vast ocean. Through experimentation and reflection, you hone your compass so that you can sail forward on the waters with a clearer sense of direction. It’s in this space of not-quite-knowing that true change happens— not in our job title, but in our self realization.

Reflection #06: For you, what possible selves are worth exploring? How might you begin to test these hypotheses?

Love and health,