Why we escaped city life and built a home in the woods

And will we regret it after the pandemic?

The Reset is a high achiever’s guide to designing a meaningful life. Today, I share a personal story many months in the making. If you like it, would you mind sharing with high achievers you know? 🙏

Of all the decisions I had made in life, inhabiting a big city was one I never questioned.

As a college junior, I took the train up from Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station to Manhattan’s Penn Station to interview at banks and management consulting firms. Donning a J.Crew wool suit and my practical pumps, I swished through glass revolving doors in Midtown and Wall Street to spend all day hopping from conference rooms to networking events.

Manhattan was impossibly glamorous. Before there was Uber or Lyft, I ducked into yellow taxis and stared out the window at the bokeh of Times Square lights. I was starry eyed about the perks of urban life: a nightly Seamless stipend, the presumed freedom from nervously watch the taxi mileage ticker (the firm would pay for my commute), Friday night happy hour at B Bar.

The city’s expansiveness was intoxicating. Participating in something so big kept me from feeling small.

Dreaming up our fate

Fast forward a decade to December 31, 2019: New Year’s Eve. Instead of partying with champagne and sparklers in Manhattan, my partner Ben and I chose to enjoy a quiet date at home.

After dinner, we sat at our coffee table and brainstormed our dreams for the upcoming year: for ourselves, for each other, and for our lives together. (I wrote up this exercise in case you’re interested in trying this with your partner)

We started by individually writing these dreams, one on each post-it note. We then categorized them into Mindy (dreams for me), Ben (dreams for Ben), and Ben + Mindy (dreams we wanted to manifest together).

One of Ben’s dreams for the year was to purchase a plot of land and build a house on the property. While we weren’t willing to give up our Manhattan home base, Ben wanted a place to pause city life and spend a long weekend coding and building.

As the clock struck midnight, neither of us predicted how differently 2020 would pan out. And little did we know that this dream would catalyze big changes.

An urgent escape

March 1st marked the first COVID-19 case in New York City. Two weeks later came the first deaths and the city shut down. Ben experienced anxiety attacks as he worked as a software engineer on pandemic relief projects. As New York hospital beds filled up and deaths mounted, we latched onto worst case scenarios. We needed to leave the city.

We rented a car, packed the essentials and our two dogs, and embarked on a 12-hour drive to Georgia where Ben’s brother lived. Being close to family was essential for our mental well-being.

While we were fortunate to be financially secure, Ben’s anxiety continued, and he put work aside for a while. We stopped checking the news obsessively and limited our device usage. We spent ample time outdoors in the backyard, soaking in the trees and sun.

The uncertainty of the pandemic took away the big things to look forward to. No trips, vacations, jazz concerts, or friend gatherings. We instead noticed and appreciated the smaller longings: a nice lunch on the patio, a bluebird perched outside the window, watching our dogs rolling around excitedly in the grass.

Stripping away the stimuli of Manhattan life gave us a new sense of calm. We were more present with each other. As introverts, we were energized by remote work and the increased control we had over our environment and time.

Exploring new territories

We did find one new use case for our smartphones: browsing Zillow listings.

It started as a thrilling side hobby. We’d look for houses and send each other the most ridiculous looking ones. When we came across a beautiful home, we’d ogle at it together, admiring the architectural details. We also browsed land plots, fantasizing about escaping to the woods or Berkshire hills. It was exciting to come across a blank canvas and superimpose our ideal lives onto it.

When we returned to Manhattan in May, we needed respite from being locked inside our apartment. Driving out of the city to scope out land plots was the perfect answer.

Over time, our search became serious. Spurred by curiosity, Ben bought books on evaluating land, structural engineering, and even the essentials of plumbing. Reading about land made owning it increasingly plausible.

On drives, we made pros and cons lists about the properties we had seen. Some plots were in beautiful parts of the country but were too underdeveloped. Others weren’t private enough; we’d be within sight of our neighbors. We found stunning views on the edges of cliffs, only to realize that building a house there would be quite an engineering feat. We even encountered a patch of land overlooking the most gorgeous rolling hills— only to discover that it was downwind of cow pastures and reeked of manure.

One day, we drove up an unpaved, muddy path to a five acre plot in Northwestern Connecticut, which we’ll call Butter Hill. As we got out of the rental car and climbed to the top of the hill, we could see the green landscape peeking up from behind the fluffy trees. The sun shone on our faces. It was quiet and still, and we could hear the chirping of birds and light rustling of leaves. The plot was completely private, enclosed behind woods, yet still gave us expansive views.

Ben reached for my hand. Butter Hill had our hearts.

Playing Jenga with assumptions

We accumulate layers of assumptions in life about who we should be, where we should live, and what a good life looks like.

In normal times, these assumptions remain buried and unquestioned. We never look down and ask “could I change the foundation I’ve built my life upon?”

The pandemic shook up and overturned the soil. I started poking at long-held assumptions in this order:

Assumption: I must live in a big city to work at high growth companies

What I realized: I can work from anywhere—a huge and rare privilege. Companies like Facebook and Google were quick to adjust their policies to accommodate remote workers. While not every tech company offered geographically flexible roles, enough did that I felt secure moving out of the city.

Assumption: I must live in a big city to have fulfilling social lives

What I realized: The alluring buzz of city life caused me to invest thinly across friendships. A brunch in West Village here, outdoor cocktails there— my social calendar filled up quickly at the expense of spending deeper quality time with the most important relationships.

Wouldn’t it be nice— I’d think whenever my mom or Ben’s family visited us— if we could spend as much time as we wanted together? It was challenging to host people overnight in our New York apartment. Though spacious by Manhattan standards, guests would stay in Ben’s office, repurposed as a bedroom with a pull-down Murphy bed. When we had friends or family over, we gave up our ability to do focused work.

Assumption: Life will suck without the conveniences of the city

What I realized: In many ways, the city’s conveniences complicated my life.

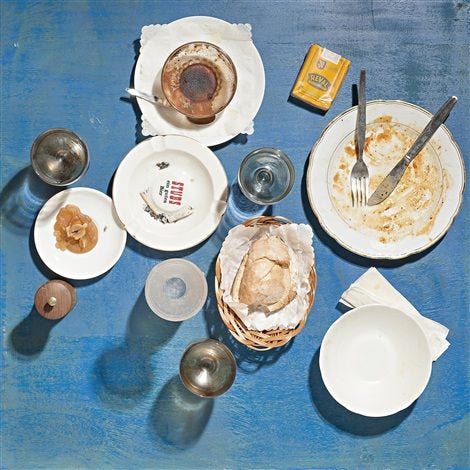

Let’s take food as an example. With 20,000 restaurants accessible by subway, each meal couldn’t just be good; it had to be exquisite enough to be shared and endorsed on Instagram. And if it wasn’t, I felt a deflated sense of regret. It was a level of privilege and dissatisfaction that left me queasy.

In a similar vein, I found myself in self-perpetuating cycles that sapped opportunities for joy. I worked a high-paying, high-intensity job, which meant no time to cook. I therefore ordered takeout and dined out on the regular, which left me no groceries for the weekend. With an empty fridge, it was hard to say “no” to brunch and dinner invitations, so I filled my weekends with more dining out with friends and acquaintances. All the while, I found myself wishing I could slow down to cook a meal with Ben and enjoy each other’s company under less hectic circumstances.

Our pandemic escape afforded us fewer conveniences but significantly more fulfillment from appreciating the smaller, more humble joys. And the things we’d truly miss— intimate jazz performances, swing dances, new gallery openings— could be savored in smaller, rarer doses via weekend drives into the city.

Assumption: I must work in a high intensity, high growth, high-income job

What I realized: As a high achiever, I held onto a specific archetype of work: sprinting at a growth company, exchanging vast quantities of my energy for vested equity. It seemed near impossible to give up this image.

Then in the fall, I did. As we closed on Butter Hill and started building our house, the dissonance between the physical image of my future life and the hectic nature of my work widened. It felt increasingly inauthentic to continue working at a growing tech company while I committed, financially and geographically, to a slower and more considered life in the Berkshires. I started planning a transition to leave my full-time job.

As I removed these assumptions one by one, the tower of my preconceived life crumpled in a heap of wooden beams. Here, I had the rare opportunity to redesign life from the ground up.

Redesigning our lives

Designing a house involves thousands of decisions. And designing a life… well, that requires an infinite number of choices, small and large.

There are two ways of making decisions: by convention and by first principles.

Making decisions based on conventional wisdom shortcuts our thought process. Under this method, we adopt what culture, society, and the people in our lives tell us is the right thing to do, implicitly or explicitly.

On the other hand, thinking from first principles means challenging socially formed assumptions and establishing our own foundation from the ground up.

First principles thinking is not always preferred or prudent. As children or adolescents, we may not have the self knowledge or agency to abandon conventions. And doing so may have caused us rejection and loneliness at a crucial time in our social development.

Now in my early thirties, I found myself with the means, confidence, and life partner to build from first principles. What were the affirmations that’d underlie the design system of this next phase of life? And how could these inform the home we were building?

Here’s what we landed on:

1. Design for everyday beauty

Why: Ben and I love design. We’re highly sensitive to the aesthetics of our surroundings. Good design and the pursuit of beauty were essential to a good life.

How this informed our home: We picked an architect whose taste we admired. In addition, 10% of our building costs were spent on massive windows throughout our home, letting in sunlight and views.

2. Quality time spent on quality relationships

Why: We want to spend slow and ample time with the people we truly care about. We value this above and beyond maintaining a broad network of acquaintances.

How this informed our home: We built a 500 square foot guest house so that friends and family (including friends with small kids) could stay comfortably without feeling like they were imposing on our space.

3. Creative work, done flexibly and remotely

Why: Ben and I both felt energized by remote work. We could control our environment and shield ourselves from the buzz of an office. We had more agency in shaping our schedule and how we spent our precious attention. And we wanted to invest this energy in exploring our most creative and fulfilling work (more on this in a future post).

How this informed our home: We built two home offices and a large basement, to be converted into Ben’s eventual workshop. To stay within budget, we traded off space. Our house isn’t particularly big (just under 2000 square feet) given the size of our property.

Grappling with fear

When I told friends and acquaintances about our move, they reacted in two ways: first, they were excited for us. Second, they asked: “But will you regret moving after the pandemic? Will you have FOMO?”

It was an excellent question, one that I was reflecting on myself.

For me, FOMO (fear of missing out) emerges from:

A lack of clarity and confidence in what I want and why. I can’t afford to miss out if I don’t know what I’m seeking. More is always better. What others have is always better. These become easy heuristics to hook onto.

A deeper, more poignant fear of not belonging. Other people are having fun without me, and I am excluded.

My twenties were characterized by rampant FOMO. After college, I worked at Microsoft in Seattle and feared missing out on life in the Bay Area. I harbored angst about the hot startup jobs and college friend hangouts I was missing out on. I started flying to San Francisco frequently on weekends and eventually moved in 2012 to join a startup called Dropbox.

After moving to New York City a few years ago, my FOMO only increased. I pursued most things that came my way: opportunities, social gatherings, new experiences. And yet, it was hard to be settled and satisfied; I was always a subway ride or short walk away from what could’ve been.

If my twenties were about saying “yes,” my thirties are about saying “not now.” I approach this decade as an editor, paring down life’s elements to reflect what I truly want —all the while, staying open to future encounters with the things I put aside.

I don’t regret the sprinting I did in my twenties. That abundance of activity was the raw material that I’m now sculpting into clearer meaning. While I was huffing and puffing on the race track, collecting accolades and experiences, I was also growing. It took slowing down and sitting on the bleachers for a while to make sense of these data points.

The unknown next chapter

In December, we broke ground and started building the foundation of our home. Week after week, we see new progress— floor beams appearing, wood frames to hold panes of glass.

As we anticipate moving in, my inner journey continues. I’ve learned to self-author my definition of a good life, one that is less encumbered by others’ expectations. I have an outline of my future life, but I don’t have everything figured out.

I sometimes lie awake at night plotting the “what if’s.” While the open questions can be daunting at times, I’ve decided to embrace the unknowns.

As poet Rainer Maria Rilke said:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given to you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

Change, no matter how thrilling and positive, is also scary. When the prospect of change rattles my heart and mind, I return to this poem by the late John O’Donohue:

For a New Beginning

In out of the way places of the heart

Where your thoughts never think to wander

This beginning has been quietly forming

Waiting until you were ready to emerge.For a long time it has watched your desire

Feeling the emptiness grow inside you

Noticing how you willed yourself on

Still unable to leave what you had outgrown.It watched you play with the seduction of safety

And the grey promises that sameness whispered

Heard the waves of turmoil rise and relent

Wondered would you always live like this.Then the delight, when your courage kindled,

And out you stepped onto new ground,

Your eyes young again with energy and dream

A path of plenitude opening before you.Though your destination is not clear

You can trust the promise of this opening;

Unfurl yourself into the grace of beginning

That is one with your life’s desire.Awaken your spirit to adventure

Hold nothing back, learn to find ease in risk

Soon you will be home in a new rhythm

For your soul senses the world that awaits you.

Indeed, this new beginning has been watching me for a while, waiting for the right moment to unfold.

Love and health,

P.S. To learn more about the details of our home building journey, subscribe to newhouse.substack.com

(Thanks to Awais Hussain, Emily Zhao, John Lanza, Matthew Vere, Art Lapinsch, Amber Williams, Halle Kaplan-Allen, Joshua Poh, Minnow Park, Ergest Xheblati, Shreedhar Manek, Kavir Kaycee, Kim-Mai Cutler, Ryan J Williams, Howard Gray, Ayomide Ofulue, and Compound for their guidance)