The Reset is a high achiever’s guide to designing a meaningful life. If you like this post, would you mind sharing with other high achievers you know? 🙏

“I feel like I’ve plateaued,” they said, glancing down.

I was meeting with a mentee who was frustrated by their career. “I’ve been a Senior Product Manager for ages. I feel like I’ve been unlucky and made bets on companies that didn’t go anywhere. And now I’m stuck here with nowhere to go.”

I sensed the disappointment, impatience, and fear.

As high achievers, we strive for the coveted promotion: a sign that the coordinates of our career are indeed moving in the right direction. Nothing seems to satisfy our desire for quantitative certainty as much as a semi-annual performance rating or title change.

We plot our trajectories as points on a curve.

In my first year after college, I got promoted twice—once every six months. As my career has advanced, the promotions are far less frequent. This can pose a dilemma for the high-achieving soul.

The intermediate gulf

As achievers, we seek and savor markers of progress. Having a clear and tangible goal drives us. Reaching it feels good and is a rare moment of pride for those of us who are hard on ourselves most days.

But growth isn’t always linear with a slope of 1.

Three years ago, as an adult in my late twenties, I learned to dance. On a Saturday in April, I walked into a Midtown dance studio to attend the Intro to Swing Dance workshop. Standing in front of a wall covered floor to ceiling in mirrors, I was in for a rude awakening —one which I always suspected but, until then, had never confirmed: I had two left feet.

It took me months of intensive lessons and daily practice to grasp the fundamentals. Rhythm, pulse, how to respond to a dance partner’s suggestions— all brand new concepts. Through studious commitment, I improved rapidly. It was exhilarating. I advanced to higher level classes at the studio. I recorded my lessons on video and saw huge differences week to week.

Then, a year later, I hit a plateau.

I still practiced several times a week. I was still mentally and physically committed to dance. But I wasn’t seeing the high slope improvement that I noticed when I was a beginner. I’d leave practices feeling frustrated by my stifled progress. The visible markers of growth had slowed. I had embarked on the intermediate gulf.

Why progress slows in the middle

What’s puzzling about being in the middle: The next set of skills requires un-learning the very behaviors that made us successful thus far.

Marshall Goldberg, executive coach and author, writes about this phenomenon in his aptly named bestseller What Got You Here Won’t Get You There. He identifies twenty-one habits that enable corporate workers to be successful— all of which need to be broken and shifted by corporate workers if they want to reach the next level of leadership.

Likewise, product leader Nikhyl Singhal elaborates on the shift in skills required to go from leader to executive leader. One’s focus shifts from being the expert to mastering key relationships and empowering a team.

Moving past the middle requires challenging the very rules that got us here. For example, swing dancers evolve from mastering specific moves to embracing improvisation. The meta-skill of improvisation requires rewiring the brain to trust our instincts the moment we hear something in the music, while letting go of the sometimes rigid instruction we’ve received. In doing so, dancers embody the dance’s core intention: to co-create a unique movement that expresses the soul of jazz music. [1]

I struggled with improvisation. I learned to dance by observing and following, with an obsessive attention to detail, what my teacher was doing. Now, I had to find my own voice in the music, to spontaneously create without being held back by the precision that I had worked so hard to cultivate. I was at a standstill.

Similarly, my mentee was mystified by the pause in career trajectory. I’m doing everything I’m supposed to do, they pondered. Why isn’t it moving me forward like it used to?

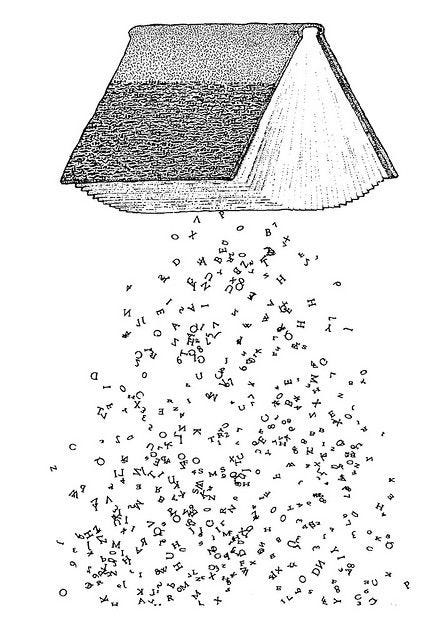

In the middle, we wrestle with the invisible and uncomfortable ways we must change. Growth happens underneath the surface; instead of a straight line, it’s ball of twine that requires patience to untangle.

The opportunity in pausing

There is a gift waiting for you in this phase of life: the potential for clarity.

When extrinsic markers of success decrease in frequency, and we’re left with the nuts and bolts of daily work, we’re compelled to confront a crucial question: Do I like what I’m doing?

When the rate of change has quieted, we may be tempted to fill the void with additional strivings, to pile on activities, network events, workshops, and training—anything to shift our coordinates on the curve our respective industries have mapped out for us. We like to distract from stillness and the jarring truths it sometimes brings.

But the stillness may be exactly what we need.

A friend of mine calls this phase the basecamp— a place of rest and preparation before embarking on one’s next expedition. In our careers, we experience stages of ascending the mountain, taking on new challenges and experiencing new heights. And there are stages where we are at a plateau: things slow down, and we have a rare chance to look inward.

Finding your way forward

Take a deep breath and ask yourself: Is this career meaningful to me?

If the answer is yes, there is a path forward. You can and will grow in necessary capacities. If your work carries meaning, trust that you will untangle that ball of twine because you enjoy the process of it. The road ahead will take time, patience, and commitment. Since the external rewards of progress are less consistent and predictable from here, see if you can unlock a more fulfilling journey by celebrating intrinsic growth.

A few ways to do this:

Join a peer community that witnesses your growth and gives you ongoing encouragement (examples include The Grand, which I help facilitate, Peer Pressure, Medley, and The Cru).

Keep a daily journal of celebration-worthy moments, a collection of situations (however small) that made you proud of how you showed up.

Share your personal growth goals with managers, mentors, and advocates. Ask them to point out moments when they notice progress.

If the answer is no, there is also a path forward. You are confronted with a trajectory of growth that is equally if not more daring than the default: designing a more worthy vocation for your one wild and precious life.

William Bridges writes in his book Transitions:

“The neutral zone is a time of inner reorientation. It is the phase of the transition process that the modern world pays least attention to. By treating ourselves like appliances that can be unplugged and plugged in again at will or cars that stop and start with the twist of a key, we have forgotten the importance of fallow time and winter and rests in music.”

Improvisation in jazz creates unexpected space between notes, causing us to wait with delicious anticipation. What feels like a plateau could be a window to pause, shift how we measure our success, and dance to life’s syncopated rhythm.

Love and health,

[1] Lindy Hop (the form of swing dancing that I’m learning) was invented by the black community in Harlem ballrooms. While the rest of society did the foxtrot and other traditional dances, black dancers were inventing something unlike they had ever seen: improvisational, inventive, swinging fire, right in the center of the ballroom. Back then, dance was a way of being and living; the moves weren’t “taught” to the original dancers. In modern times, those of us who didn’t grow up with the dance honor the legacy of original dancers by learning in classrooms. If you’re curious to learn more about swing dance, watch Alive and Kicking (a documentary) or read this autobiography by Frankie Manning, one of the original Harlem dancers.

Thank you to Ryan W, Philip H, Emily Z, Claire Z, Rajat M, Kushaan S, and Compound for providing feedback on the draft.